Wanting to get a closer look at village life in Fiji and an idea of what life was like prior to European contact, I made the necessary preparations for a trip out to the island of Nacula, one of the furthest in the island chain of the Yasawas group. I stopped off at several islands along the way and made friends with a German traveler name Henrick, who agreed to make the journey all the way to Nacula with me. For the last leg of the trip we had a local fisherman drop us off at a tiny cove on the southern edge of Nacula, and he pointed us to a trail that would presumably lead us towards the village itself.

The path took us over the spine of the island where only a tall grass grew, above which we could see the sweeping panoramas of this and other islands. After some distance the path dipped down into a valley and we began to see signs of farming, planted rows of sweet potato, banana and bread-fruit trees.

Then, through some foliage and into a sunny clearing we could make out a number of thatch-roofed homes and wonderfully colorful laundry hung out to dry. It was deftly quiet, and though we had been anticipating it, Hendrick and I found ourselves at a a loss as to how to make first contact with the village and its inhabitants.

For some time we just stood there and I had just begun to suspect that no one was around, when from out of one of the huts came a joyous voice which proclaimed - Bula! There was no mistaking its meaning of welcome, and we replied with the same. A woman emerged with a flower print dress and instructed us in awkward English that before we are allowed to visit the village we must first meet its chief. We soon found ourselves following her lead down the narrow footpaths that meandered between the fifty or so identical homes. By each dwelling we were met with the same greeting and families gathered at their open doors and windows and smiled out at us as we passed.

The Meeting House

At the other end of the village there was a slightly larger structure built of the same materials as the others, which we were invited to enter and then asked to sit on the many reed mats that were spread across the floor. This we were told was the village meeting house. The woman who we had followed asked us to wait here for the chief

and instructed us that when he came we should make a sevusevu, a small customary gift. Fortunately we were prepared and I had with me a small amount of

kava which I understood was the traditional gift on such occasions.

Kava bundle at market

Kava bundle at marketAfter a while the chief entered and sat cross-legged before us on the floor. He was a robust middle-aged man in a t-shirt, but he still maintained some degree

regalregality. He graciously accepted our gift of

Kava, which I presented by putting on the floor in front of him.

Henrick

Henrick and I introduced ourselves, and he invited us to look around at the many pictures of him and his family that adorned the walls of the meeting house. In one was his brother who we learned was a captain of a large ship and could be seen posing in his uniform. In another there was a few of his nephews proudly displaying a rugby trophy. Our meeting with the chief was brief. At its end he said that he would appoint his niece as our guide for as long as we chose to stay in the village and he introduced the young girl that had been waiting at the entrance, then he left.

I looked up at what appeared to be a large bone or tusk hanging from one of the rafters of the meeting house. When I asked our new guide about it, she explained that this was the

Tabua, or the tooth of a sperm whale. In Fiji they are presented to important guests and exchanged at weddings, births, and funerals she explained. The particular

tabua hanging in this meeting house was very old and showed that it had been worn by the many times it had changed hands.

We soon found out that our new guide, though shy, spoke a fair amount of English. She attended a boarding school on one of the "closer islands", Mondays through Fridays, at which half of her instruction was in English.

We followed her out and began our stroll through the rest of the village. On the way we passed what we were told was the home of the "oldest man" in the village. He was half way up a tree nailing something down when we met him. He was pretty limber for an old-timer. I shook his outstretched hand and he gave me a broad toothless smile, and said

Bula of course. I told him that I was a history teacher, here to study Fiji's history. I asked if a lot had changed since he was a child in the village. He got what I had asked, and through our guide who translated he said

"

When I was little we would cut the bananas before they were ripe. It would take us over a week to sail our small boats to the mainland. The bananas would ripen along the way and be ready by the time we made it to the market. Now we wait until they are ripe before we cut them and we use an outboard motor." So, that pretty much sums that up.

Our next stop was the "store" which was really just a couple of shelves in a corner of one of the village huts. To see how little was actually available for purchase in the village drove home just how self sufficient it really was. Only a few staples such as tea, sugar, and flour were imported from the mainland. The rest of life's necessities were either fished from the sea, plucked from a tree, or were harvested in their village's gardens. This village apparently planted only three crops - sweet potato, pineapple, and bananas, and none of these required much looking after.

The church was by far the biggest structure in the village, but was still quite small. It was made of concrete, with windows along its side which opened to let in the sea breeze. Outside sitting under the shade of some

marvelous trees, the likes of which I have never seen before, there was a group of women who, hearing of our arrival, had laid out their wares on blankets for us to survey. Our guide explained that these women make jewelery and such out of shells, which they sell to the boatmen who bring the goods to their village store, who in turn sell it to the shops on the mainland. They seemed eager to skip the middle man in this case, but it was still a remarkably low pressure sale. I purchased a large

nautilus shell.

Near the coast at one end of the village there was a group of young men

busy around a bunch of materials sprawled out on the ground. To my excitement I found out that they were constructing one of the village homes which I learned was called a

bure. They were a fun bunch and were happy to let us investigate their progress. I brought out my video camera and one of the more gregarious guys gave me a full narration of the methods and materials involved in creating one of these traditional structures. It was pretty amazing to see it all come together. In what seemed like no time the framework was completed and they were explaining to me how the reeds were woven together and tied up to create the walls and ceiling.

The thing that I found really fascinating was what the villagers did with these homes when a hurricane struck. They told me that their traditional

bures could be

untied,

disassembled and covered, keeping the materials protected. When it was over they would simply reassemble their

bures. However, the newer construction that included boards, nails, and concrete would be torn apart and have to be completely rebuilt.

Like the rest of my experiences in this village, this got me to thinking about the merits of simplicity. Wandering around the village was an interesting look at life in a comparatively isolated corner of the world. There were of course signs of change everywhere. Several homes had electricity which was supplied from a generator. Some of the boats appeared to be made out of fiberglass. People had radios and other things bought from the mainland. But not much!

About 130 million years ago, in the mid-to-late Jurassic period, the land that today comprises New Zealand was torn away from the southern supercontinent of Gondwana.

About 130 million years ago, in the mid-to-late Jurassic period, the land that today comprises New Zealand was torn away from the southern supercontinent of Gondwana.

A walk through New Zealand's remaining native forests is in some ways like a real life "Jurassic park", and gives some indication of what the world was like millions of years ago. The progenitors of New Zealand's forests stemmed from Gondwana and its existing species have developed in relative isolation from the changes that have occurred in forests elsewhere in the world.

A walk through New Zealand's remaining native forests is in some ways like a real life "Jurassic park", and gives some indication of what the world was like millions of years ago. The progenitors of New Zealand's forests stemmed from Gondwana and its existing species have developed in relative isolation from the changes that have occurred in forests elsewhere in the world.  In some areas massive kauri trees with diameters of over twelve feet wide still scrape the sky. Much of the forest is filled with the dense foliage of strange tree ferns that look to those who are not used to them like overgrown house plants.

In some areas massive kauri trees with diameters of over twelve feet wide still scrape the sky. Much of the forest is filled with the dense foliage of strange tree ferns that look to those who are not used to them like overgrown house plants. In the absence of mammals, birds came to occupy a dominant role in New Zealand's ecosystem. Up until just a few hundred years ago the largest herbivore in the New Zealand's forests was the moa, a giant flightless bird which reached 12 feet in height and weighed up to 550 pounds. Prior to human contact the Moa's only predator was the Hasst's eagle, the largest predatory bird to have lived, with a wing span of up to ten feet.

In the absence of mammals, birds came to occupy a dominant role in New Zealand's ecosystem. Up until just a few hundred years ago the largest herbivore in the New Zealand's forests was the moa, a giant flightless bird which reached 12 feet in height and weighed up to 550 pounds. Prior to human contact the Moa's only predator was the Hasst's eagle, the largest predatory bird to have lived, with a wing span of up to ten feet. Today New Zealand's bird life remains exotic, with ground dwelling parrots, kiwis and other flightless birds. I found it particularly strange to be in an alpine environment in which snow occurs year round and at the same time being surrounded by group of Keas, large parrots that have adapted to living in the mountains.

Today New Zealand's bird life remains exotic, with ground dwelling parrots, kiwis and other flightless birds. I found it particularly strange to be in an alpine environment in which snow occurs year round and at the same time being surrounded by group of Keas, large parrots that have adapted to living in the mountains.

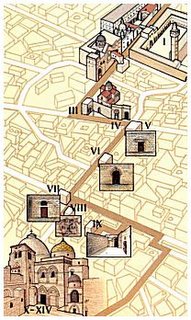

The Dome of the Rock was built in 691 C.E. by Caliph Abd al-Malik, half a century after the death of the Muslim Prophet Muhammad. It is the most visible structure in Jerusalem. It is not a mosque, but a shrine. Like the Ka'ba in Mecca, it is built over a sacred stone. This stone is believed to be the very place from which the Prophet Muhammad ascended into heaven during his Night Journey to heaven. It is the oldest Muslim building which has survived intact in its original form. It also boasts the oldest surviving mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca) in the world.

The Dome of the Rock was built in 691 C.E. by Caliph Abd al-Malik, half a century after the death of the Muslim Prophet Muhammad. It is the most visible structure in Jerusalem. It is not a mosque, but a shrine. Like the Ka'ba in Mecca, it is built over a sacred stone. This stone is believed to be the very place from which the Prophet Muhammad ascended into heaven during his Night Journey to heaven. It is the oldest Muslim building which has survived intact in its original form. It also boasts the oldest surviving mihrab (niche indicating the direction of Mecca) in the world. Adding to the tension, according to Judaism this same stone is the site where Abraham fulfilled God's test to see if he would be willing to sacrifice his son Isaac (Muslims believe that this event involved Abraham's other son Ishmael and occurred in the desert of Mina where millions of Muslims offer pilgrimage every year). According to Jewish tradition, this was also the rock upon which the Ark of the Covenant was placed in the First Temple. During the existence of the Second Temple, the stone was used by High Priest who offered up incense and sprinkled the blood of sacrifices on it during the Yom Kippur Services. Rabbinic legend also alleges that the entire world was created from this stone, hence the name אבן השתייה, or Foundation Stone.

Adding to the tension, according to Judaism this same stone is the site where Abraham fulfilled God's test to see if he would be willing to sacrifice his son Isaac (Muslims believe that this event involved Abraham's other son Ishmael and occurred in the desert of Mina where millions of Muslims offer pilgrimage every year). According to Jewish tradition, this was also the rock upon which the Ark of the Covenant was placed in the First Temple. During the existence of the Second Temple, the stone was used by High Priest who offered up incense and sprinkled the blood of sacrifices on it during the Yom Kippur Services. Rabbinic legend also alleges that the entire world was created from this stone, hence the name אבן השתייה, or Foundation Stone.